This article originally appeared on Buddhistdoor Global on April 8, 2016.

Thangka paintings are Tibet’s most plentiful and portable form of sacred art. Less known and rarely seen are the highly prized appliqué thangkas. In fact, when I first discovered them in 1992 and expressed an interest in learning to make them, few Tibetans in Dharamsala had ever seen one.

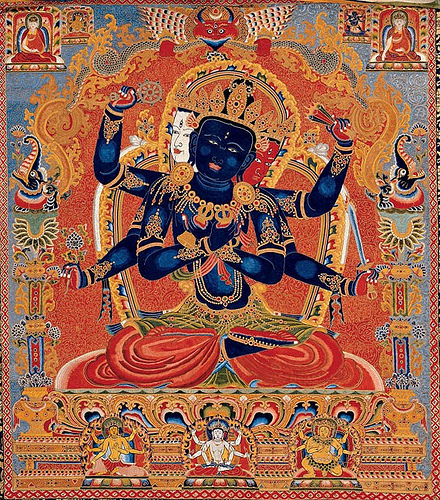

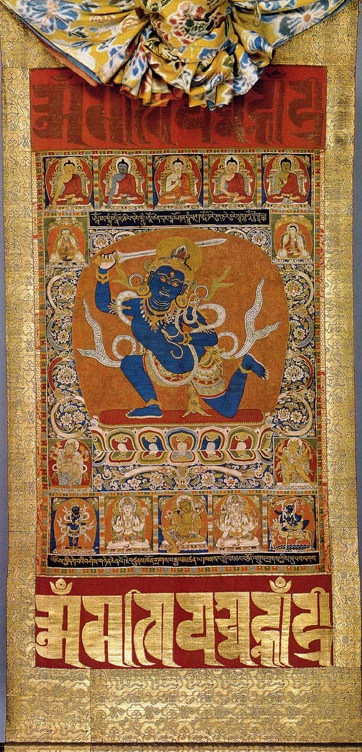

A thangka is a two-dimensional, rollable form of art—a scroll—illustrated with images of spiritual masters, enlightened beings, role models, and symbols of our Buddha nature. In most thangkas, the picture is painted on cotton canvas and then framed in brocade fabric. In some thangkas, however, not only the frame but the picture itself is constructed from fabric.

The earliest known textile thangkas were 13th-century embroideries and tapestries produced in China on the basis of Tibetan paintings. Within a century or two, thangkas of hand-stitched silk appliqué were being created inside Tibet. No one knows for sure how this artistic evolution occurred, but it was undoubtedly an outgrowth of complex relationships among the nations of central and eastern Asia in the first half of the second millennium.

Over the centuries, power in this area changed hands many times. At times, the Mongols held sway over the whole region, while in other periods, the Chinese or Manchu had control. And from 1038–1227, the Tangut empire was an important force in what is today northwest China. Often, the nation which held temporal power looked to Tibetan lamas for spiritual guidance.

Chinese silk played an important role in managing and expressing these relationships. Silk came into Tibet as imperial tribute and commercial trade from at least as early as the Tang dynasty (618–907) and perhaps much earlier. A Sino-Tibetan treaty from 760 records an annual tribute of fifty thousand “pieces” of silk from the Chinese emperor to the Tibetan court at Lhasa (Reynolds 1995, 146).

The only indigenous weaving materials in Tibet were wool and yak hair. Silk was significantly more precious. In fact, silk was used as a currency. The price of a horse, for example, is recorded as having been anywhere from twenty to forty bolts of silk, depending on the quality of the horse and the time period (Reynolds 1995, 146 and 1997, 188).

In an article on patronage and religious practice in China and Tibet, Valrae Reynolds (former curator of Asian art at the Newark Museum and one of the few people to have written about Tibetan appliqué) describes the flourishing of artistic activity from the 11th to 13th centuries, as religious teachers founded monasteries with the support of “princely” families. From documents of this period, it emerges that “one of the popular ways to gain religious merit was to donate fine silk for the use of an esteemed teacher of a Buddhist monastery” (Reynolds 1997, 189). In this way—through tribute, commerce, and investment—silk satins, damasks, and brocades began to fill the treasuries of Tibet.

When the Mongols took over, consolidating control of China after 1279, they adopted many aspects of the destroyed Tangut court’s religious connection with Tibet, giving lamas great power over religious and cultural affairs and promoting artistic ventures that incorporated Tibetan Buddhist themes and styles. The use of silk to create sacred art grew out of these fluctuating Tangut-Mongol-Tibetan-Chinese interconnections.

It was during this period that textile copies of Tibetan paintings began to be produced in China, using Chinese techniques of weaving and embroidery. Reynolds notes that these silken images held “greater cachet than the paintings they were copied from” (Reynolds 1995, 147).

Art historian Michael Henss explains that these early “pictorial embroideries, tapestries, and brocades fall in between established art historical domains in two ways: they cannot be classified as paintings, nor are they textiles in the usual sense; Chinese by technique and origin, but Tibetan by subject and composition, [they were] presented by the imperial court to Tibetan religious officials and visitors, to their monastic enclaves in China and monasteries in Tibet . . .” (Henss 1997, 206). Henss also writes: “From the historical background, the regular flow of Tibetan art to China and Chinese art to Tibet between the late thirteenth and the late fifteenth centuries seems still to be underestimated” (Henss 1997, 214).

At some point, probably in the 14th century, the Tibetans were sufficiently inspired by the Chinese textile interpretations of their paintings to begin creating their own original textile masterpieces. To do so, they employed indigenous appliqué techniques, which were already being used to embellish ritual dance costumes, saddle blankets, and throne covers and to decorate the colorful tents and awnings that dotted the landscape for festivals and picnics. In collaboration with Tibet’s greatthangka painters, the country’s finest tailors were able to adapt these techniques to the more delicate and sacred imagery of thangkas.

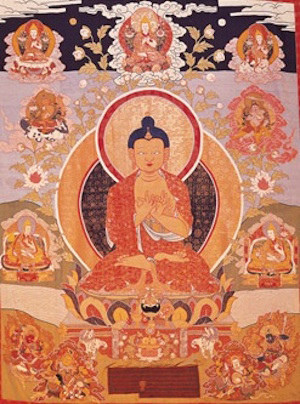

Textual records indicate that several giant appliqué thangkas were made in the early 15th century at Gyantse monastery in Tibet (Henss 1997, 214). And in 1468, the great thangka painter Menla Dhondup was commissioned by the first Dalai Lama to create a giant silk image of the historical Buddha, Shakyamuni, for display on the nine-story thangka wall of Tashilhunpo monastery. The wall was specially built for the occasional display of giant thangkas before crowds of devotees.

Monumental thangka depicting the Buddha of

the Future, Maitreya, flanked by the Eighth Dalai

Lama, Jamphel Gyatso, and his tutor, Yongtsin

Yeshe Gyaltsen. Commissioned by the Eighth

Dalai Lama for the benefit of his tutor and the

posterity of the Buddhist faith. 1793, silk appliqué,

Norton Simon Museum. From

threadsofawakening.com

Appliqué thangka production increased in the 16th century and spread throughout the region in the 17th and 18th centuries. Eventually, appliqué thangkas were being produced not only in Tibet itself, but also in the neighboring countries of Mongolia, Bhutan, and Ladakh.

Many of Tibet’s appliqué thangkas were destroyed during the 1950s and ‘60s, along with so many monasteries, texts, and cultural assets. For a few decades, this art form became largely dormant as Tibetans re-established themselves in exile and religion was suppressed within Tibet. In recent years, however, a thriving production has re-emerged among the exile community in India and Nepal, and some large appliqué thangkas have also been made within Tibet itself, including the giant Tsurphu thangka project managed by Terris and Leslie Nguyen Temple.

The prestige of fabric thangkas that began with Chinese textiles based on Tibetan paintings continues today with the uniquely Tibetan appliqué form. In the 2008 documentary Creating Buddhas: the Making and Meaning of Fabric Thangkas, Tibetologist Glenn Mullin notes, “For us, painting and sculpture are the two finest forms of art, but for Tibetans appliqué and embroidery are an even higher art.” Valrae Reynolds concurs by saying, “It’s kind of counterintuitive to the Western idea where painting and sculpture is high art and something made out of textile is craft. But in the Tibetan sense, an appliquéd thangka is the most wonderful, highest thing that you can create.”

As an American woman, privileged to have learned this ancient, interculturally generated textile tradition from Tibetans in India, I am honored to carry it forward into the 21st century and, with the support of my Tibetan teachers and colleagues, to expand its reach into the Western world.

Leslie Rinchen-Wongmo is a textile artist, teacher, and caretaker of the sacred Tibetan tradition of silk appliqué thangka. Trained by two of the finest living masters of this rare art form, she stitches pieces of silk into fabric mosaics that bring the transformative figures of Buddhist meditation to life. Encouraged by His Holiness the Dalai Lama to make this art relevant across religions and cultures, Leslie created the Stitching Buddhas Virtual Apprentice Program to help women around the world integrate their spiritual and creative paths. She is a member of the Dakini As Art Collective and author of the forthcoming book, Threads of Awakening: the Sacred Power of Tibetan Textile Art.

References

Henss, Michael. 1997. “The Woven Image: Tibeto-Chinese Textile Thangkas of the Yuan and Early Ming Dynasties.” In Chinese and Central Asian Textiles: Selected articles from Orientations 1983-1997, 206–19. Hong Kong: Orientations Magazine Ltd.

Reynolds, Valrae. 1995. “The Silk Road: From China to Tibet – and Back.” In Chinese and Central Asian Textiles: Selected articles from Orientations 1983-1997, 146–53. Hong Kong: Orientations Magazine Ltd.

———. 1997. “Buddhist Silk Textiles: Evidence for Patronage and Ritual Practice in China and Tibet.” In Chinese and Central Asian Textiles: Selected articles from Orientations 1983-1997, 188–99. Hong Kong: Orientations Magazine Ltd.

Creating Buddhas: the Making and Meaning of Fabric Thangkas. 2008. DVD, directed by Isadora Gabrielle Leidenfrost. Madison, WI: Soulful Media.