For every hundred painted thangkas, there’s maybe one appliqué thangka.

— Valrae Reynolds, author and curator

For us, painting and sculpture are the finest forms of art, but for Tibetans, appliqué and

embroidery are an even higher art.

— Glenn Mullin, Tibetologist, writer, translator

What led an American woman to learn a sacred Tibetan art so rare that many Tibetans have never even seen it?

And what can this art teach us about our own journey to awakening?

I am finally writing a book about Tibetan appliqué and my unexpected quest to master this sacred art. Part art book, part memoir. A first-draft snippet from the memoir part follows. I’d love your help in making it as fascinating and beneficial as it can be. Please read with gentle curiosity, then email me your comments and questions.

Thanks in advance!

Leslie

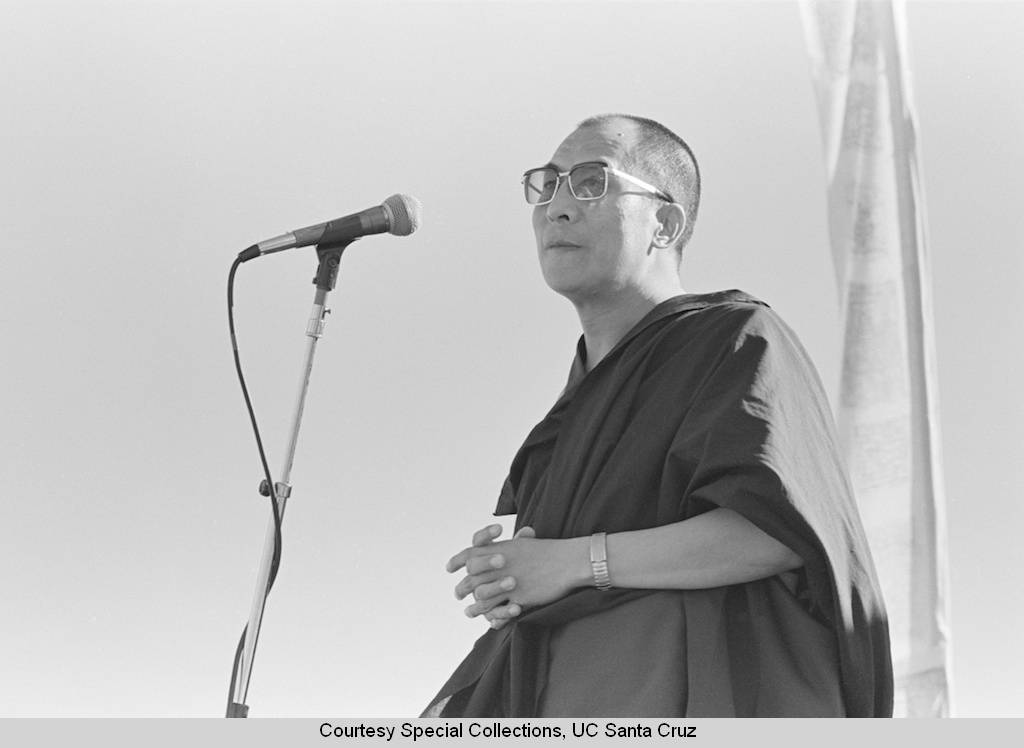

First Contact

I first saw His Holiness the Dalai Lama in 1979 when I was in college and he was making his first visit to the US. I don’t think I knew who he was. I don’t know if anyone around me did either.

Over in India and Nepal, western hippies and students had discovered the Tibetans the decade before. They’d traveled overland, by bus, heading east from Europe. The Hippie Trail was a 20th century silk road through Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan (or alternatively through Syria, Jordan, and Iraq). Rather than commerce, these modern explorers were trading in experience, discovering entirely new ways of being. Upon reaching India, some had taken vows to become monks. Many were attending teachings, doing retreats, studying Tibetan with lamas.

But I didn’t know that yet. I only found out years later after taking my own journey, by air, in the late 1980s, when travel was still rough and uncommon but was more accessible than before (largely due to the Lonely Planet guidebooks, the bible of the backpack traveler, which had been created by a couple of those early Hippie Trail overlanders).

I and my classmates at the University of California, Santa Cruz had been in utero when the Chinese occupation overtook Lhasa and the Dalai Lama was forced to flee his country, followed by 100,000 of his compatriots. By 1979, His Holiness and the Tibetan refugees had been resettled in India and Nepal for 20 years. A generation of Tibetan children had been born in exile. Inside Tibet, while we UCSC students were children, Tibetans had suffered religious repression, nomad collectivization, and starvation and had endured the Cultural Revolution with their Chinese occupiers. Thousands of monasteries had been destroyed and tens of thousands of monks and nuns killed. The people had been forced to denounce the Dalai Lama, renounce their vows, and even to kill and shame one another.

We students had been raised in prosperous cities and suburbs in a period of free expression, empowerment, abundance, and experimentation. UCSC was at the cutting edge of that experimentation, exploring new modes of education, evaluation, and fields of study.

Egalitarian relationships were promoted and students were on a first-name basis with professors. Idyllic redwood forests, rolling hills, and pastures were our classrooms, looking out over a spectacular bay and some of the best surfing in California.

Eastern spirituality had entered our awareness from an early age and was an ingredient in the human potential milieu in which we immersed ourselves. The Esalen Institute was just down the road with its mind-expanding ideas and beautiful hot tubs, open to the public after midnight, clothing discouraged. Most of our soaks were in simpler surroundings, nearby in the redwood clad hills of the Santa Cruz mountains.

We were insatiably curious and at least some of us were oriented toward growth in every aspect of our lives. So when we saw the flyers announcing that a Tibetan holy man was coming to speak on the East Field, we flocked to see him with the same enthusiasm we would have taken to a Grateful Dead concert or a walk in the woods on magic mushrooms or a vision quest.

This was His Holiness’ first visit to the United States. He was not greeted by statesmen but was welcomed to college campuses around the country. I have no idea how our small, nonconformist university got on the itinerary. And I don’t remember what His Holiness talked about that day (but there’s a recording and I will add something from it!) or what my first impression was. He spoke in Tibetan, translated into English by an interpreter, though his English was already remarkably good.

It was a sunny day, and I knew I was in the right place. Little did I know where that “place” really was and that a seed planted there would grow into a path.

***

I’m writing a book and I’d like your help in making it as fascinating and useful as possible. You’ve just read a draft snippet. Your loving feedback will help me refine it. Please email me your comments and questions. Let me know what touched you and what lost you.

With gratitude overflowing,

Leslie